Celebrating our African historical

personalities, discoveries, achievements and eras as proud people with rich

culture, traditions and enlightenment spanning many years.

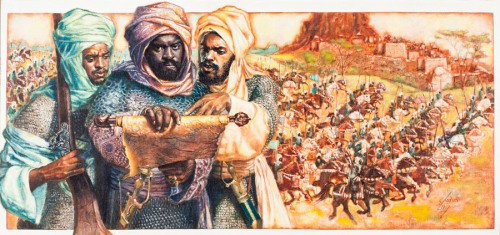

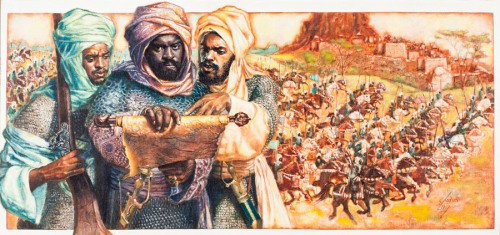

Famous Historical Muslims of African/Black Origin

Islamic civilization currently encompasses every

culture, ethnicity, race, and language on the planet. The pages of Islamic

history are filled with the emergence of many different ethno-linguistic

groups, from regions as far apart as West Africa and Central Asia, as important

political and cultural forces, which greatly impacted the direction of Islamic

civilization. Unfortunately, despite this reality, Muslim history has often

been presented as a series of accomplishments revolving around Arabs, Persians,

and Turks, to the exclusion of all other groups. The rich histories of hundreds

of Muslim ethnic, racial, and linguistic groups have too often been overlooked

or overshadowed by this mistaken approach towards Muslim history and

expropriated by the master narrative which seeks to identify Muslim history

with a very specific cultural and geographic context.

The marginalization of the historical legacy of

African Muslims needs to be understood within this broader context. Black

Muslims, or Muslims of African origin, have played—and continue to play— a

particularly important role in Islamic civilization as ascetics, reformers,

leaders, revolutionaries, and scholars. In many ways, the egalitarian and

diverse spirit of Islam is most clearly manifested in this history, the impact

of which extended far beyond Africa and the influence of which has left a

significant historical legacy. Yet, many Muslims are ignorant of this rich history.

How many Muslim youths are familiar with the story of Usāma ibn Zayd? When we speak of revolution and justice,

who today speaks of the Zanj rebellion, an ultimately unsuccessful struggle,

colored by messianic tendencies, waged by African Muslims in order to transform

an unjust social and political order? Moreover, in theological circles, while

we examine the works of Ibn al-Qayyim, al-Ghazālī, and

Ibn Arabī—volumes of which have

been translated and are readily available—the reformist thought of Usmān dan Fodio, Nānā Asmā’u and Amadou Bamba remains a mystery to most Muslims,

many of whom have scarcely heard the names of these great scholars from West

Africa. It is important for many Muslims to reclaim this history, which has too

often been forgotten or marginalized. This process of reclamation begins with

the recognition of those individuals who shaped this history and who

contributed to Islamic civilization. Among the most important of these men and

women are:

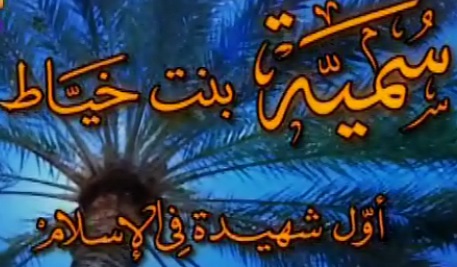

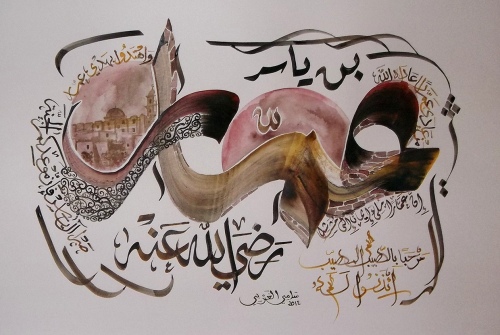

Sumayya b. Khayyāṭ (d. 615).

Sumayya was one of the first women to embrace Islam during the Meccan period,

shortly after the declaration of the Prophet’s mission in 610 A.D. She was the

wife of Yāsir b. ‘Āmir and mother to ‘Ammār b. Yāsir. Originally a slave, she was later freed following

the birth of her son. Sumayya, her husband, and her son were the first instance

in the history of the faith of an entire family embracing Islam. Due to the

staunch opposition of the Quraysh tribe of Mecca to the new faith, however,

Sumayya and her family (lacking tribal protection, since they were of humble

origins) bore the brunt of the persecution of the Meccans as they attempted to

destroy the nascent Islamic faith. Due to their refusal to abandon their new

faith, both Sumayya and Yāsir were

publicly tortured before being executed (in front of their son, ‘Ammār) by the Qurashi tribal chieftain Abū Jahl ‘Amr b.

Hishām in 615 A.D. As such,

Sumayya is considered to be the first martyr in Islam according to Muslim

tradition.

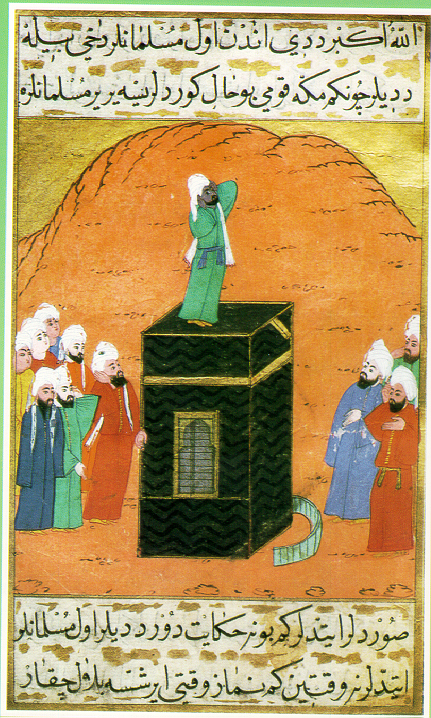

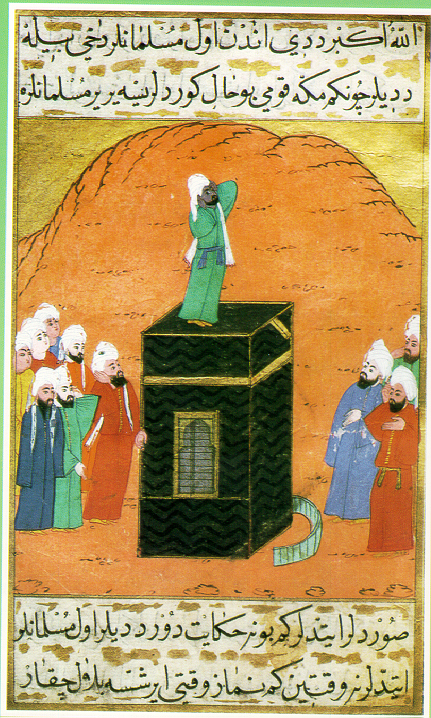

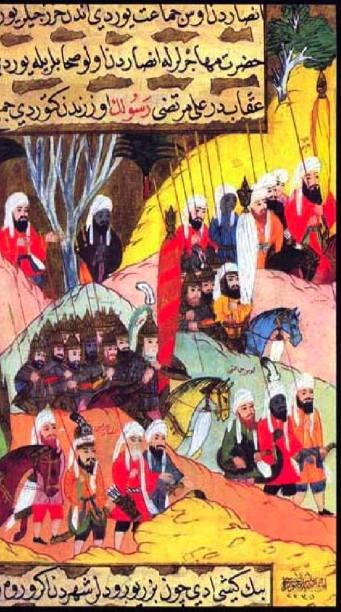

Bilāl ibn Rabāḥ (d. 640). Bilāl was an

emancipated Ethiopian slave who became one of the closest and most trusted

companions of the Prophet Muhammad and the first muezzin (caller

to prayer) in Islam. During the time of the Prophet, he was appointed to the

important position of the custodian of the treasury (bayt al-māl). He

participated in most of the Prophet’s expeditions and battles and proved his

dedication to the Islamic cause on numerous occasions. Following the death of

the Prophet, he was among the most important partisans of ‘Alī b. Abī Tālib and supported his claims to the caliphate. He died

in Syria around 640 and is buried in Damascus.

Umm Ayman (d. 650). Umm

Ayman, also known as Barakah, was an emancipated Ethiopian slave and a renowned

companion of the Prophet Muhammad and was one of the few individuals who

closely knew the Prophet from his birth until his death. She was married to

Zayd b. al-Ḥāritha, the adopted son of

the Prophet, and was among the closest and most trusted confidants of the

Prophet Muhammad. She was among the earliest converts to Islam and

participated in the battle of Uhud, caring and tending for the wounded. She

died in 644 and is buried in the Jannat al-Baqī’ cemetery in Medina.

‘Ubāda b. al-Ṣāmit b. Qays al-Khazrajī al-Anṣārī (d.

654). An early Companion of the

Prophet Muhammad, ‘Ubāda was

one of the earliest converts to Islam in Medina and participated in all the

major battles of the Prophet, including Badr and Uhud. During the time of the

Prophet, he was among the most respected Companions and was appointed to a

position of authority more than once by the Prophet. ‘Umar b. al-Khaṭṭāb (d. 644), the second caliph, had immense respect for

‘Ubāda and described him as a “man whose value exceeds that of 1000 men.” During the early caliphate, he was appointed by Abū Bakr (r. 632–634) and

‘Umar (r. 634–644) as

an emissary to the Cyrus of Alexandria (d. 641), the Byzantine prefect of

Egypt, and he played an important role as a general in the Arab conquest of

Egypt in 642. A pious individual, he was highly critical of the wealth and

ostentation of certain individuals—especially the governor of Syria, Mu‘awiya

b. Abī Sufyān (d. 680)—whose

Islamic credentials he felt were lacking. He died in 654 and was buried in

Jerusalem, where his tomb became an important site for local visitation.

‘Ammār b. Yāsir (d. 657). ‘Ammar was the son of the martyred Sumayya and Yāsir (mentioned above). As one of the earliest converts

to the faith, he was also viciously persecuted and tortured by the Meccans

before migrating to Medina (according to some sources, he also made the earlier

migration to Abyssinia in 616). He is considered among the most senior of the

Prophet’s Companions, having converted early and participated in every major

event and expedition during the lifetime of the Prophet. Following the

Prophet’s death, he was among the most committed partisans of ‘Alī b. Abī Ṭālib’s claim

to the caliphate and played a significant role as a scholar within the early

Muslim community, transmitting many of the Prophet’s teachings. He was a major

vocal critic of the third caliph, ‘Uthmān b. ‘Affān, and opposed many of the latter’s policies, which he believed were unjust. ‘Ammār was

killed in the Battle of Siffin (657) while fighting for the fourth caliph, ‘Alī b. Abī Ṭālib, against the army of Mu‘āwiya b. Abī Sufyān in Syria. He is widely considered by Muslims, to

have been one of the closest and truest companions of the Prophet Muhammad and

his Family, and thus as a paragon of righteousness in the early Muslim

community. His tomb in Syria was a major site of visitation for pilgrims from

across the Islamic world until its destruction by Salafist-Jihadists in March

2013.

Usāma b.

Zayd (d. 674). The son of

Zayd ibn al-Hāritha and Umm Ayman, Usāma b. Zayd was among the closest companions of the

Prophet Muhammad, and was the youngest individual ever appointed as a military

general during the lifetime of the Prophet, leading a military force—which included some of the highest-ranking

companions—when he was only seventeen years old. Following the Prophet’s death,

he played an important role as a general, especially in the military campaigns

against Byzantium, and is best known for his neutral stance during the civil

wars that took place during the caliphate of ‘Alī b. Abī Tālib (r. 656-661). He died around 674 and is buried in

Medina.

For more on these early Islamic figures and Companions

of the Prophet, see:

Asma Afsarrudin, The First Muslims: History

and Memory (2007)

Muhammad Yusuf Kandhalawi, Hayatus-Sahaba: The

Lives of the Sahaba(2007)

Ella Landau-Tasserson (trans.), The History of

al-Tabari, Vol. 39: Biographies of the Prophet’s Companions and Their

Successors: al-Tabari’s Supplement to his History (1998)

Martin Lings, Muhammad: His Life Based on the

Earliest Sources (2001)

Muhammad b. ‘Alī al-Jawād al-Husaynī (d. 835). Considered the ninth Imām by the Twelver Shi’i tradition, Muhammad al-Jawād was from the lineage of the Prophet and one of the

most important Alid figures during his time. His mother, al-Khayzaran (also

known as Sabika), was of Nubian or East African origin and was an important

figure in her own right, with many Muslims considering her among the most

virtuous and knowledgeable women of her era. Muhammad al-Jawād undertook the responsibility of the Imamate while

only 8 years old and died at the young age of 25. Although he lived in

turbulent times and despite his youth, he played an important role—religiously

and intellectually—as the leader of the Shi‘i community. In addition to being

revered as the Imām of the Age by Twelver Shi’is, he is also highly respected and revered by Sunnis

as a religious scholar and one of the most prominent leaders of the Ahl al-Bayt

in his time. He died in 835—probably poisoned on the orders of the Abbasid

caliph—and was buried in Baghdad next to his grandfather Mūsa al-Kāẓim (d.

799), where his shrine remains an important place of visitation for the

faithful. Among the many pieces of wisdom that have been ascribed to him is the

following:

“Modesty is the ornament of poverty, thanksgiving is

the ornament of affluence and wealth. Patience and endurance are the ornaments

of calamities and distress. Humility is the ornament of lineage, and eloquence

is the ornament of speech. Committing to memory is the ornament of [hadith]

narration, and bowing the shoulders is the ornament of knowledge. Decency and

good morale is the ornament of the intellect, and a smiling face is the

ornament of munificence and generosity. Not boasting of doing favors is the

ornament of good deeds, and humility is the ornament of service. Spending less

is the ornament of contentment, and abandoning the meaningless and unnecessary

things is the ornament of abstention and fear of God.”

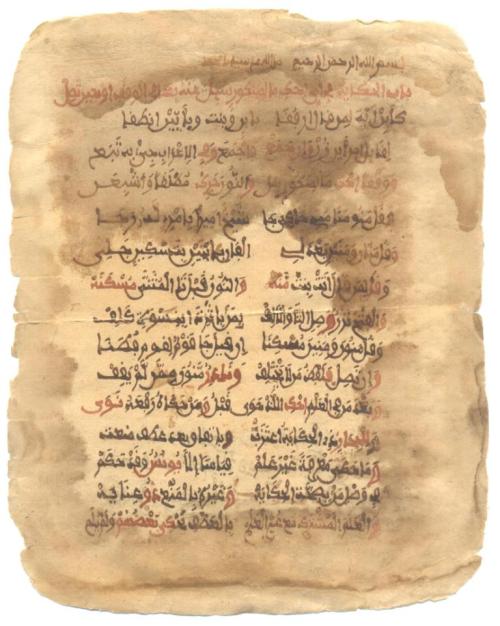

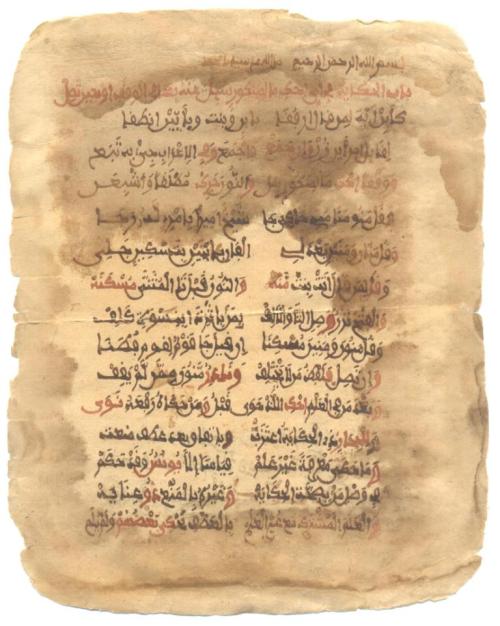

العفاف زينة الفقر، والشكر زينة الغنى، والصّبر زينة البلاء والتواضع زينة الحسب، والفصاحة زينة الكلام، والحفظ زينة الرواية، وخفض الجناح زينة العلم، وحسن الأدب زينة العقل، وبسط الوجه زينة الكرم، وترك المنّ زينة المعروف، والخشوع زينة الصلاة، وترك ما لا يعني زينة الورع

[Narrated in Kashf al-Ghummah fī Ma‘rifat

al-A’immah (Volume

3, p. 139 in the Beirut 1985 edition) by Abū al-Ḥasan ‘Alī b. ‘Isa

al-Irbilī (d. 692/1293) and

al-Fuṣūl al-Muhimmah fī Ma‘rifat

al-A’immah (p. 261

in the 1988 Beirut edition) by Nūr al-Dīn ‘Alī b. Muḥammad (d. 885/1451), known as Ibn al-Sabbāgh]

For further reading:

Shaykh al-Mufid, Kitab al-Irshad: The Book of

Guidance into the Lives of the Twelve Imams (2007)

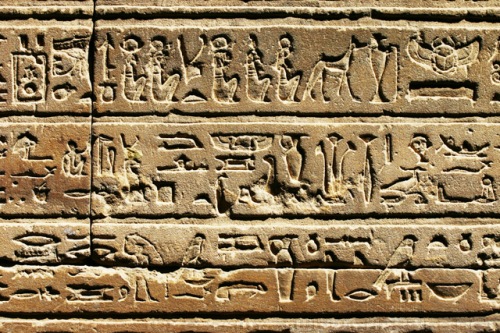

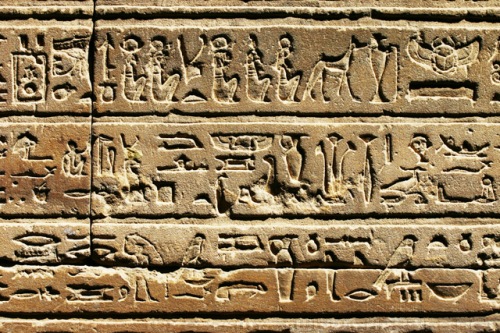

Dhūl Nūn Abū al-Fayḍ Thawbān b. Ibrāhīm al-Miṣrī (d. 859). One of the most prominent early mystics in the Islamic

world, Dhūl Nūn originated from Nubia and was the teacher of another

prominent early Sufi, Sahl al-Tustarī (d.

896). His teachings emphasized the central role of gnosis or ma‘rifa in

attaining higher spiritual truths. He has also been associated with Hermetic

philosophy and alchemy, which resulted in his being tried for heresy by the

Abbasids in Baghdad in the 840s. According to the tenth-century historian

al-Mas‘ūdī (d. 956), Dhūl Nūn was “an

ascetic and a philosopher who pursued a course of his own in religion. He was

one of those who elucidate the history of these temple-ruins (barabi).

He roamed among them [the temples] and examined a great quantity of figures and

inscriptions.” This interesting statement is most likely a reference to Dhūl Nūn’s interest in the hieroglyphs and inscriptions on the

many temples he encountered in Egypt, which he believed possessed an inner

spiritual meaning and perhaps a trace of the Hermetic sciences of the past.

For more, see:

Farid al-Din Attar and A.J. Arberry (trans.), Muslim

Saints and Mystics: Episodes from the Tadhkirat al-Auliya’ (1990)

Annemarie Schimmel, Mystical Dimensions of

Islam (1975)

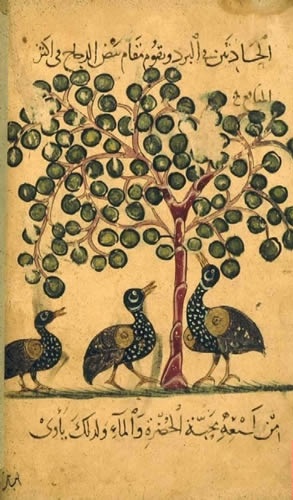

“al-Jāḥiẓ” Abū ʿUthman ʿAmr b.

Baḥr (d.

869). Originally from Basra,

al-Jāḥiẓ is renowned as one of the most important litterateurs

in Islamic history. In addition, he was an accomplished Mu‘tazalite theologian,

poet, philosopher, grammarian and linguist. He authored about 200 books on

various subjects ranging from religio-political polemics to treatises on

rhetoric and zoology. Among his most famous works is his Risālat Mufākharat al-Sūdan ‘ala

al-Biḍān, an impassioned defense of the superior qualities and

accomplishments of the peoples of sub-Saharan and East Africa.

For more, see:

Charles Pellat, The Life and Works of

al-Jahiz: Translations of Selected Texts(1969)

Abū

al-Misk Kafūr (d. 968). Originally an East African slave, Kafūr rose to become a military commander and eventually sultan

of the Ikhshidid dynasty, which included territory encompassing modern-day

Egypt, Sudan, Libya, Eritrea, Palestine, Syria, Lebanon, Turkey, Cyprus, Iraq,

Jordan, and the Hejaz. An effective ruler, he was able to defend his realms

from incursions from the Fatimids, Hamdanids and Qaramita. He was also a major

patron of the arts and scholarship, with the famous Arab poet al-Mutannabi (d.

965) being among the many poets whom he patronized.

For more, see:

Marshall Hodgson, The Venture of Islam,

Vol 1 (1974)

Hugh Kennedy, The Prophet and the Age of the

Caliphates (2004)

Abd Allāh b. Yāsīn (d.1059).

Jurist, theologian, reformist, and one of the founders of the al-Murābitun (Almoravid) movement and dynasty, which ruled

North Africa and Iberia between 1080 and 1147. He was an important disciple of

the Maliki scholar Waggag b. Zallu al-Lamti (d. 1054) and played a central role

in the Islamization of the Berber tribes of West Africa. It was ‘Abd Allāh b. Yāsīn who played a critical role in transforming the Almoravid

movement from a religious organization into an important political and military

force.

For more, see:

Ronald A. Messier, The Almoravids and the

Meaning of Jihad (2010)

H.T. Norris, H.T. “New evidence on the life of

‘Abdullah B. Yasin and the origins of the Almoravid movement.,” The

Journal of African History, Vol. 12, No. 2 (1971), pp. 255–268.

Al-Mustanṣir bi-llāh (d.

1094). Fatimid Isma’ili

Imam-Caliph. He was born to a Sudanese mother and his caliphate lasted for

about 60 years, the longest of any caliph in the Islamic world. His reign

witnessed intellectual efflorescence, the consolidation of Ismai’li thought and

doctrine, and the expansion of the Fatimid da’wa into regions

such as Yemen and India. It was during his period as caliph that the Fatimids

repelled the attempted Seljuk invasion of Egypt and briefly held sway over

Baghdad in 1058.

For more, see:

Paul Walker, Exploring an Islamic Empire:

Fatimid History and its Sources(2002)

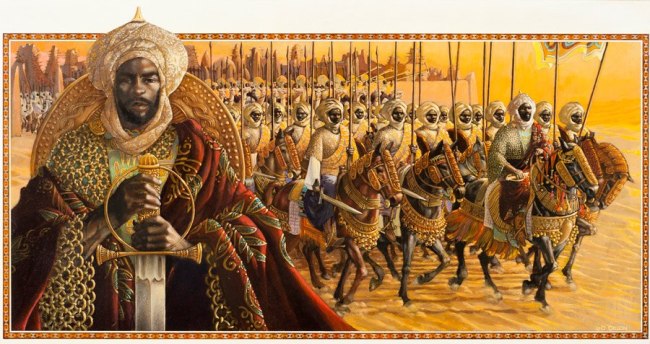

Mansa Mūsa (d.1337).

Emperor of the Malian Empire in West Africa famously known for his wealth,

patronage of Islamic scholars, and magnificent architectural projects. His

reign is remembered as one of the most prosperous of any monarch in the history

of Muslim West Africa. His fame was so extensive and his wealth was so renowned

that his name was well-known in Western Christendom and he was featured quite

prominently in the Catalan Atlas of 1375 (image below).

For more, see:

Nawal Morcos Bell, “The age of Mansa Musa of Mali:

Problems in succession and chronology”, International Journal of

African Historical Studies 5 (1972): 221–234.

Nehemia Levtzion and John F.P. Hopkins, eds. Corpus

of Early Arabic Sources for West Africa (2002)

Nehemia Levtzion, “The thirteenth- and

fourteenth-century kings of Mali”, Journal of African History (1963):

341–353

P. James Oliver, Mansa Musa and the Empire of

Mali (2013)

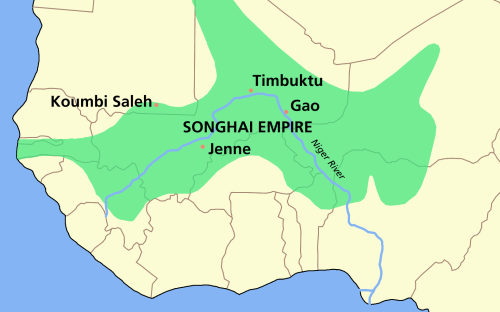

Sonni Alī (d.1492). Military strategist, conqueror, and

founder of the Songhai Empire in West Africa. In comparison with his

successors, he promoted a syncretic religious policy in his kingdom, which led

to strong opposition from the religious establishment.

For more, see:

Patricia McKissack and Frederick McKissack, The

Royal Kingdoms of Ghana, Mali and Songhay: Life in Medieval Africa (1995)

Askia Mohammad I (d. 1538). The greatest emperor of the Songhai

dynasty who expanded and consolidated the empire. He introduced important

political reforms and extended the boundaries of the Songhai. He was also an

important patron of Islamic scholarship and made Islamic law one of the

cornerstones of his religious policy and aligned himself very closely with the

religious scholars of Timbuktu. His reign witnessed the massive expansion of

trade networks across the region.

For more, see:

John O. Hunwick, Timbuktu and the Songhay

Empire: Al-Sadi’s Tarikh al-Sudan down to 1613 and other contemporary documents (1999)

John. O Hunwick, Sharia in Songhay: The

Replies of al-Maghili (1985)

Mustafa Zemmouri/Estevanico (d.1539).

Also known as Esteban de Dorantes. Enslaved

by the Portuguese and later the Spanish in his native Morocco, Estevanico was

among the earliest travelers in the Americas, taking part in exploration

expeditions in regions corresponding to modern-day Cuba, Mexico, Florida, New

Mexico, Arizona, and Texas. As such, he is considered to be the first

African-born individual to have set foot in continental North America.

For more, see:

Carolyn Arrington, Black Explorer in Spanish

Texas: Estevanico (1986)

Robert Goodwin, Crossing the Continent,

1527-1540 (2008)

Rayford Logan, “Estevanico, Negro Discoverer of the

Southwest: A Critical Reexamination”, Phylon 1 (1940):

305-314.

Elizabeth Shepherd, The Discoveries of Esteban

the Black (1970)

Idrīs Alouma (d.

1603). Administrator, military leader, and ruler of the Bornu-Kamen Empire in

Central Africa. He is remembered for his Islamic piety, legal reforms, and

prosperous rule. He introduced many legal and administrative reforms, grounded

in Islamic law, implemented an Islamic court system and patronized major

construction projects of mosques and madrasas throughout his kingdom. Alouma, a

pious Muslim, played an important role as a patron of Islamic scholarship and

the ulema’ with whom he was closely allied and, following the fall of the

Songhai empire, became the most powerful Muslim monarch between the Niger and

the Nile. He is also credited with an expansion of trade routes and networks

that increased the economic prosperity of the empire. Alouma’s reign also

witnessed the establishment of important diplomatic contacts with the Ottoman

Empire, who sent an embassy to his court. The latter sent him military advisers

that helped introduce important reforms of his army by introducing gunpowder

technology, which contributed to his success on the battlefield against his

enemies. Like Mansa Musa, Alouma is known for having performed the pilgrimage

to Mecca. His military competence, administrative reforms, encouragement of

learning and diplomatic maneuvers allowed Idrīs Alouma to transform Bornu from one kingdom among

many in Central Africa into perhaps one of the most important sub-Saharan

Islamic states.

For more, see:

John O. Hunwick. “Songhay, Bornu and Hausaland in the

sixteenth century”, in J. Ajayi and M. Crowder (eds.), The History of

West Africa (1971): 202-239

Dierk Lange, A Sudanic Chronicle: the Borno

Expeditions of Idrīs Alauma(1987)

B.G. Martin, “Mai Idris of Bornu and the Ottoman

Turks, 1576-1578,”International Journal of Middle East Studies 3 (1972):

470-490

Ahmad Baba (d. 1627). Perhaps the greatest Muslim scholar to ever emerge

from Timbuktu, Ahmad Baba was descended from a long line of Muslim scholars and

lived during the Songhai era and was renowned as a jurist, grammarian,

theologian, political writer, and historian, writing over 40 works during his

lifetime. Following the conquest of Timbuktu by the invading Moroccan forces of

Ahmad al-Mansur in 1591, Shaykh Ahmad Baba was accused of fomenting a rebellion

against the occupiers and was subsequently taken in chains as a prisoner to the

Moroccan capital of Marrakesh in 1593. While in Marrakesh, he was treated less

harshly due to his scholarly credentials and he continued to teach law and

issue legal rulings but was effectively confined by his royal captors to the

city limits. By this time, he had become recognized as one of the most senior

jurists and scholars of his age. Among his most important works are Nayl

al-Ibtihaj, his biographical dictionary in which he compiles a list of the

major Maliki scholars from North and West Africa during this period, Jalb

al-Ni’ma wa Daf’ al-Naqma bi-Mujanabat al-Wulat al-Dhalama, a work on

political theory emphasizing the role of justice as a basis for the legitimacy

of rulers, as well as his compilation of legal rulings. His personal library

consisted of several thousand books, many of which have survived extant.

Following the death of Ahmad al-Mansur in 1603, Ahmad Baba performed the

pilgrimage to Mecca before returning to Timbuktu where he continued his work as

a practicing Maliki jurist and theologian until his death in 1627.

For more, see:

Hunwick, J.O. “A New Source for the Biography of Ahmad

Baba al-Tinbukti (1556-1627)”, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and

African Studies (1964) 27: 568–593

Hunwick, John O. “Ahmad Baba on Slavery.” Sudanic

Africa 11 (2000): 131–139

Lévi-Provençal, E.. “Aḥmad Bābā.” Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Edited by: P.

Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel, W.P. Heinrichs. Brill

Online, 2015

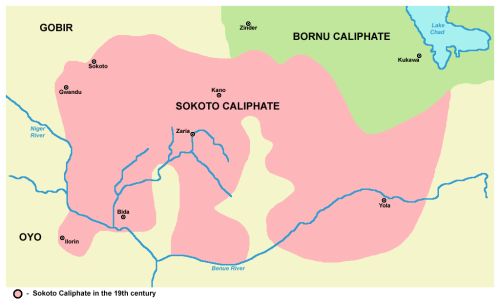

Shehu Usmān dan Fodīo (d.1817). Also

known as ‘Uthman b. Fudi, he was a religious scholar, jurist, ascetic,

reformer, revolutionary, and founder of the Sokoto Caliphate in northern

Nigeria. An ethnic Fulani residing in Hausaland, Dan Fodio was a jurist of the

Maliki school and an adherent of the Qadariyya Sufi order. He placed heavy

emphasis on political and religious reform, believing the Muslim states of West

Africa to have deviated from the principles of justice and righteousness that

were enshrined in Islamic law. He was particularly opposed to the oppressive

social and fiscal practices that had come to dominate Hausaland and found

strong support for his reforms among the peasantry in particular. He

spearheaded a major campaign of religious revivalism and reform in order to

rectify this state of affairs and led a major Fulani armed uprising against the

rulers of Hausaland. His efforts culminated in the establishment of the Sokoto

Caliphate, a theocratic state based strictly on Islamic law. He then waged war

against neighboring states, bringing them under his authority and implementing

his reforms in the conquered regions. Shortly after his establishment of the

caliphate, Dan Fodio, while continuing to hold the title of Commander of the

Believers (amir al-mu’mineen) delegated his authority to his son

(Muhammad Bello) and retired from public life, spending most of his time

engaged in preaching, teaching and writing. He was a prolific writer, authoring

numerous books and treatises on politics, philosophy, theology, mysticism, and

law in both the Arabic and Fulani languages. He was a strong advocate of education

and literacy, for both men and women, and several of his children (including

his daughter, mentioned below) were important scholars in their own right.

Shehu Usman dan Fodio was perhaps the most important

Muslim reformist leader in West Africa during the nineteenth century. This was

due both to his scholarship and his role as a political leader, which

reinvigorated West African Islam with a renewed sense of purpose. Most

importantly was Dan Fodio’s founding of the Sokoto caliphate which brought the

Hausa states and some neighbouring territories under a single central

administration for the first time in history.

For more, see:

Mervyn Hiskett, The Sword of Truth: The Life

and Times of the Shehu Usuman Dan Fodio (1972)

S. J. Hogben and A. H. M. Kirk-Greene, The

Emirates of Northern Nigeria(1966)

Hugh A.S. Johnston, Fulani Empire of Sokoto (1967)

Ghislaine Lydon, On Trans-Saharan Trails:

Islamic Law, Trade Networks, and Cross-Cultural Exchange in Nineteenth-Century

West Africa (2012)

Ibraheem Sulaiman, The Islamic State and the

Challenge of History: Ideals, Policies, and Operation of the Sokoto Caliphate (1987)

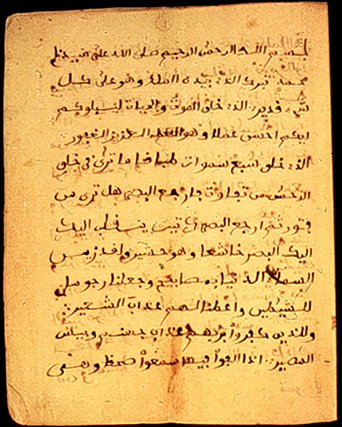

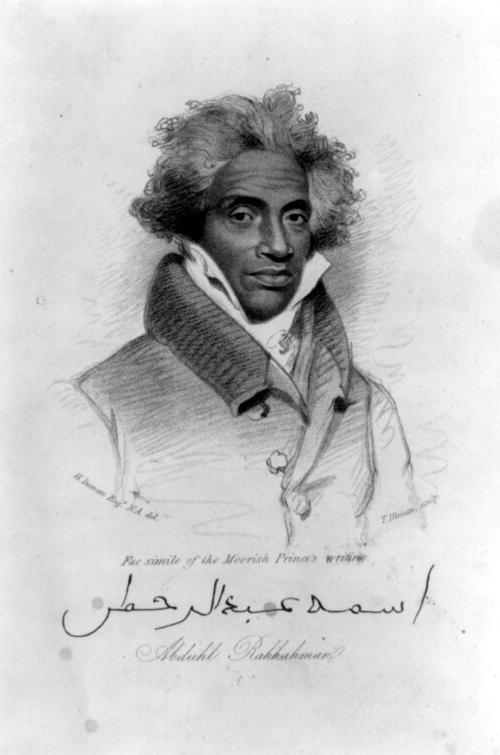

Ibrahim Abd al-Rahman (d. 1829). Born into a noble family in West Africa and trained in

the Islamic sciences, studying in the famous scholarly center of Timbuktu,

Ibrahim was enslaved in his twenties by the British and ended up in New Orleans

in the Americas. After spending nearly 40 years as a slave, he was released by

the order of US President John Quincy Adams after the Sultan of Morocco–Mulay Abd

al-Rahman ibn Hisham–had requested his release. He returned to Africa and died

there.

For more, see:

Terry Alford, Prince among Slaves (2007)

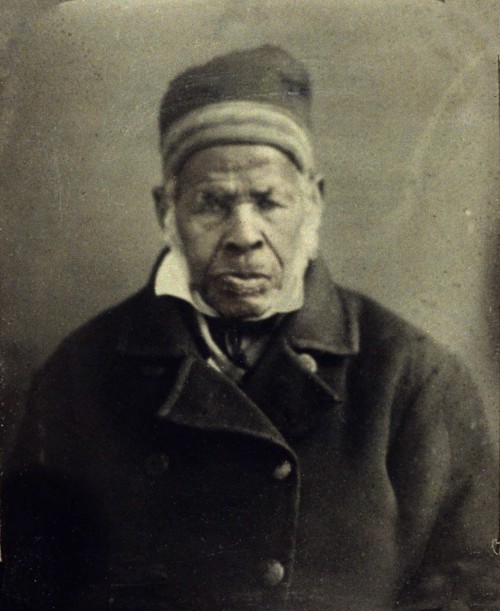

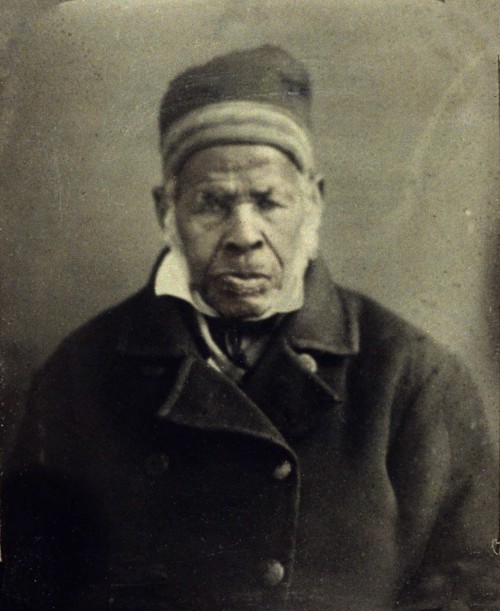

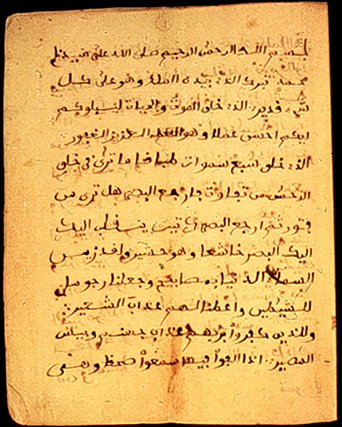

Omar ibn Said (d. 1864). Omar ibn Said was a Muslim author and

theologian who was born in modern-day Senegal. In 1807, at the age of 37, he

was enslaved and brought to North Carolina in the continental United States.

Although he officially converted to Christianity around 1820, widespread

evidence suggests that he continued to secretly practice Islam. He left behind

important writings, including significant religious treatises, an autobiography

and an annotated Arabic translation of the Bible. Fourteen manuscripts of his,

all written in Arabic, survive. His works demonstrate his familiarity with the

Qur’an, Islamic theology, and Christianity. He is buried in Bladen County,

North Carolina. As someone who left behind important traces of his life and

thought, he is one of the most renowned of the African Muslims who were

enslaved and brought to the Americas. For more, see:

Nānā Asmā’u (d. 1864). She was the daughter of Shehu

Usmān dan Fodīo (d.

1232/1817), a jurist, reformer, ascetic and the founder of the Sokoto

caliphate. Although many have assumed that her fame is linked solely with her

father’s career, it should be

underscored that Nānā Asmā’u was an

important poet, historian, educator, and religious scholar in her own right who

continued to play a major role in the political, cultural and intellectual

developments in West Africa for nearly 50 years after her father’s death. Nānā Asmā’u, both a Mālikī jurist and a Sufi mystic of the Qādirī order,

was devoted to the education of Muslim women and continued the reformist

tradition of her father, believing that knowledge held the key to the

betterment of society. She established the first major system of schools and

other institutions of learning throughout the Sokoto caliphate.

Nānā Asmā’u was

fluent in four languages (Arabic, Fula, Hausa, and Tamacheq Tuareg) and was a

very prolific writer, composing over 70 works in subjects such as history,

theology, law, and the role of women in Islam. As an ardent advocate of the

participation of women in society and as a result of her broad-based campaign

to empower and educate women, she was one of the most influential women in West

Africa in the 19th century. She was also heavily involved in the politics of

the Sokoto caliphate, acting as an adviser to her brother, the Sultan of Sokoto

Amīr al-Mu’minīn Muḥammad

Bello (r. 1232–1253/1817–1837). To end this brief overview of Nānā Asmā’u’s

extraordinary life and contributions, I leave you all with a lengthy quote

summarizing her legacy and accomplishments:

“In addition to teaching students in her own

community, [Nana Asma’u] reached far beyond the confines of her compound

through a network of itinerant women teachers whom she trained to teach

isolated rural women. An accomplished author, Asma’u was well educated,

quadrilingual (in Arabic, Fulfulde, Hausa, and Tamachek), and a respected

scholar of international repute who was in communication with scholars

throughout the sub-Saharan African Muslim world. Asma’u pursued all these

endeavors as a Sufi of the Qadiriyya order, but the driving factor in her own

life and that of the community was their concern for the Sunna, the exemplary

way of life set forth by the Prophet Muhammad. With the Sunna orchestrating the

lives of its members, Asma’u’s Qadiriyva community sought to serve through

teaching, preaching, and practical work, focused on a spiritual life in the

world, while rejecting materialism.

Asma’u was a pearl on a string of women’s scholarship

that extended throughout the Muslim world. This chain of women scholars

originated long before Asma’u’s lifetime and stretched over a wide geographic

region from the Middle East to West Africa. The network of women’s scholarship

contemporaneous to Asma’u is but the tip of the iceberg. It did not spring

forth fullblown, but was nurtured over successive generations as an integral

part of the aim of Islam: the search for communion with God through the pursuit

of Truth. Education and literacy have been hallmarks of Islam since its

inception. Any society that impedes equitable access to salvation by

controlling or limiting who can get an education eschews the tenets of Islam;

so for the Qadiriyya community to which Asma’u belonged, to deny women equal

opportunity to develop their God-given talents was to challenge God’s will.”

[Beverly B. Mack and Jean Boyd, One Woman’s

Jihad: Nana Asma’u, Scholar and Scribe (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana

University Press, 2000), pp. 1–2]

For more on Nānā Asmā’u, see:

Nana Asma’u, Collected Works of Nana Asma’u. Jean

Boyd and Beverly B. Mack eds. (1997)

Jean Boyd, The Caliph’s Sister: Nana Asma’u,

1793-1865, Teacher, Poet and Islamic Leader (1990)

Beverly B. Mack and Jean Boyd, Educating

Muslim Women: The West African Legacy of Nana Asma’u, 1793-1864 (2013)

For more, see:

Nana Asma’u, Collected Works of Nana Asma’u. Jean

Boyd and Beverly B. Mack eds. (1997)

Jean Boyd, The Caliph’s Sister: Nana Asma’u,

1793-1865, Teacher, Poet and Islamic Leader (1990)

Beverly B. Mack and Jean Boyd, One Woman’s

Jihad: Nana Asma’u, Scholar and Scribe (2000)

Beverly B. Mack and Jean Boyd, Educating

Muslim Women: The West African Legacy of Nana Asma’u, 1793-1864 (2013)

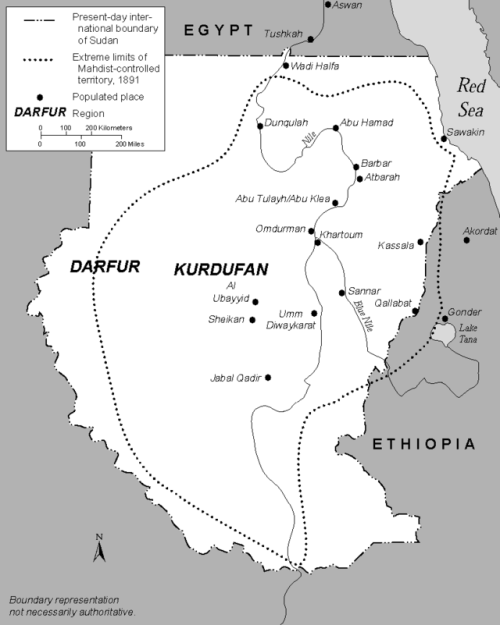

Muḥammad Aḥmad ibn ‘Abd Allāh “al-Maḥdī” (d.1885).

Sudanese reformist, mystic,

revolutionary, and anti-colonial leader who led a major rebellion against the

Turco-Egyptian and British forces in Sudan and managed to establish a large

state in most of the country. He proclaimed himself the Mahdi, or messianic

redeemer, in 1881 and declared that he was divinely-guided and received

inspiration from God. As a reformist, he should be understood as belonging to

the same broader 19th-century trend which had produced individuals such as

Usman dan Fodio, although he made more controversial claims about the nature of

his own authority, which, in addition to being a consequence of his own

mystical-religious ideas, should be understood in the context of the messianic

environment that had taken root in Sudan during this period. The success of his

rebellion made him one of the most renowned anti-colonial leaders of the 19th

century.

For more, see:

Dominic Green, Three Empires on the Nile: The

Victorian Jihad, 1869-1899(2007)

Fergus Nicoll, The Sword of the Prophet:The

Mahdi of Sudan and the Death of General Gordon (2004)

John Obert Voll, “The Sudanese Mahdi: Frontier

Fundamentalist,” International Journal of Middle East Studies 10

(1979): 145–166

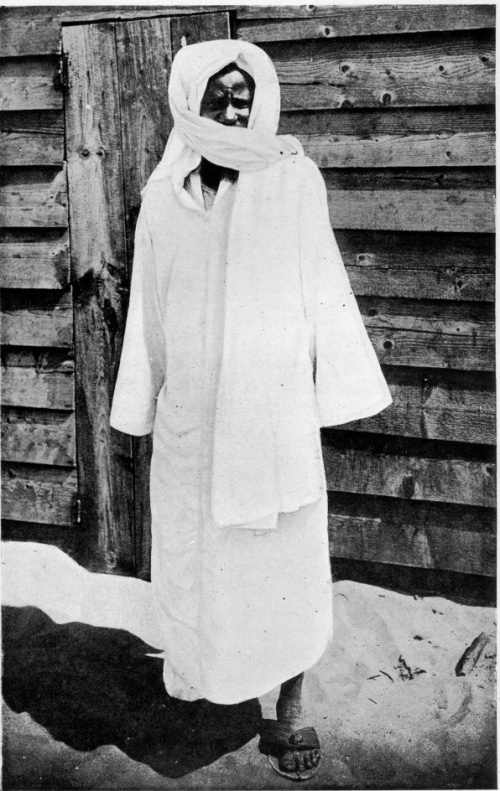

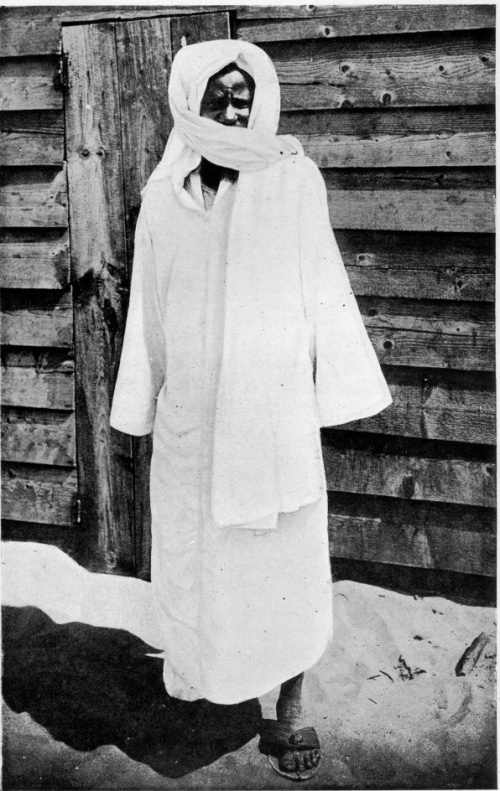

Amadou Bamba (d. 1927). Shaykh Amadou Bamba, also known as Khādim al-Raṣūl (“Servant of the Prophet”), was a Senegalese Muslim religious leader, ascetic

and mystic who founded the Murīdiyya

tarīqa/religious brotherhood in 1883. He sought to

transform the religious and social sphere in order to bring society in line

with his conception of the values and principles of the Prophet Muhammad. His

followers considered him to be the religious renewer, or mujaddid, of the age.

Shaykh Amadou Bamba’s works emphasized hard work, perfection of

morals/character, charity, humility, and meditation. In addition to being a

prominent scholar and reformist, he also led a non-violent struggle against

French colonialism in West Africa which led to his severe persecution by the

French colonial authorities throughout his life; despite this, his commitment

to non-violent resistance was unwavering. The Murīdiyya order he founded now has over 4 million

adherents in Senegal and Touba—the city

established by Amadou Bamba as the movement’s center—remains

a major site of visitation for his followers.

For more, see:

Cheikh Anta Babou. Fighting the Greater Jihad:

Amadu Bamba and the Founding of the Muridiyya of Senegal, 1853-1913. Ohio

University Press (2007)

Cheikh Tidjane Sy, La confrérie sénégalaise

des Mourides, Paris 1969

Dumont, La pensée

religieuse de Amadou Bamba, fondateur du mouridisme

sénégalaise, Dakar 1975

Marty, Les Mourides

d’Amadou Bamba, Paris 1913

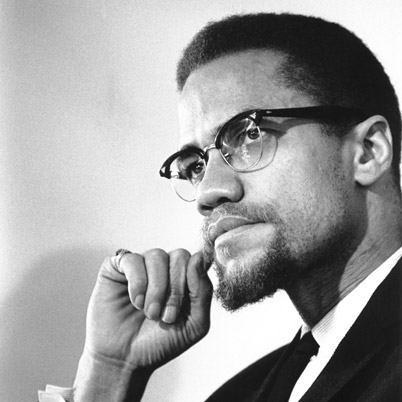

Malcolm X (d.1965).

American Muslim revolutionary, public speaker, and civil rights activist.

In 1964, he embarked on a journey to Mecca and Africa that proved to be both a

political and spiritual turning point in his life. This further convinced him

that it was necessary to place the American Civil Rights Movement within the

broader context of a global anti-colonial struggle, embracing national

self-determination and pan-Africanism. It was during his Hajj/pilgrimage to

Mecca that he converted to Sunni Islam and changed his name to El-Hajj

Malik El-Shabazz.

After his epiphany at Mecca, Malcolm X returned to the

United States more optimistic about the prospects for peaceful resolution to

America’s race problems. He believed that Islam provided the vision necessary

to resolve the racial problems in the US. It was during this period, upon his

return from Mecca, that he was reconciled with Martin Luther King Jr.

Tragically, just as Malcolm X appeared to be embarking on an ideological

transformation with the potential to dramatically alter the course of the Civil

Rights Movement, he was assassinated. His legacy has been profound and

continues to exert itself in various ways in the American Muslim community and

beyond.

For more, see:

Saladin Ambar, Malcolm X at Oxford Union:

Racial Politics in a Global Era(2014)

George Breitman, ed. Malcolm X: Selected

Speeches and Statements (1994)

Malcolm X, The Autobiography of Malcolm X: As

Told to Alex Haley (1987)

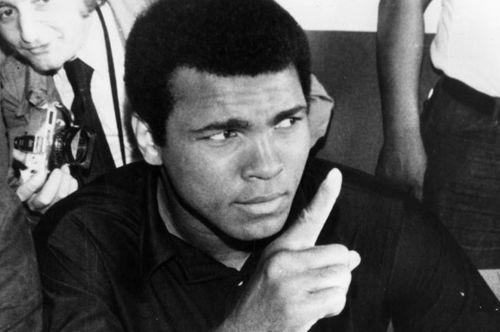

Muhammad Ali (d. 2016). Perhaps one of the most widely recognized sports

personalities of the 20th century, Muhammad Ali became boxing’s

world heavyweight championship at the age of 22, after his defeat of Sonny

Liston. Although he formally adopted Sunni Islam in 1975, he was previously

affiliated with the Nation of Islam and was highly influenced by one of its

former ministers, Malcolm X (d. 1965). For decades, Muhammad Ali has been a

major advocate and activist for racial justice and religious freedom. He refused

to be conscripted into the US army in 1967, invoking his religious beliefs as

well as his opposition to the war in Vietnam; this transformed him into an icon

of the anti-war movement. His major fame as a boxing champion, as well as his

status as a conscientious objector, made him a figure of international renown

and perhaps the most famous American Muslim during the 20th century.

And, just so we remember that this powerful legacy of

black and African Muslims being a major driving force behind the contributions

of the Muslim community (both in the US and globally) is alive and well, let us

honor those who are still active in our own day:

Amina Wadud (b. 1952). Amina Wadud is one of the most prominent and active

intellectuals in the United States. She converted to Islam in 1972 and has

played a major role in the American Muslim community ever since. Drawing on her

impressive scholarly credentials (receiving advanced degrees from the US as

well as studying at al-Azhar in Egypt), Wadud has led the way as a progressive

Islamic reformist, publishing the profoundly influential Qur’an and

Woman: Rereading the Sacred Text from a Woman’s Perspective in 1982.

In addition to her work in gender and women’s studies and her contributions to

Islamic scholarship in the US over the past several decades, Dr. Wadud is also

a prominent activist, having founded the non-governmental organization “Sisters

in Islam.” She has also participated in countless international forums

addressing issues of women’s rights, Islamic reform, and interfaith relations.

In August 1994, she gave the Friday sermon (khutba) in Cape Town, South Africa

and in March 2005 she led Friday mixed-gender congregational prayers in

Manhattan, making it the first time in the history of American Islam that a

woman led Friday prayers. Through her role as a public figure and as an

intellectual, Dr. Wadud continues to exercise a major influence upon American

Islam, especially in progressive circles.

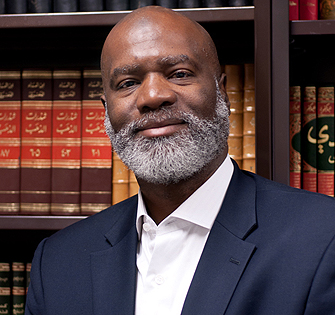

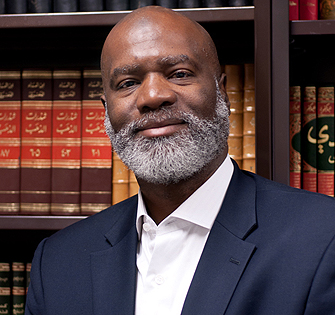

Sherman Abd al-Hakim Jackson (b. 1956). Sherman Jackson is among the most influential Muslim

intellectuals in the United States. As a scholar who works comfortably within

both the American academy and the field of classical Islamic jurisprudence, Dr.

Jackson has been a figure of major importance in the past several decades. His

work on Islamic theology and legal theory has been path-breaking in many ways

and his contributions to the academic study of Islamic law has been recognized

internationally. His book, Islam and the Problem of Black Suffering (2009),

is a singular achievement and demonstrates how deeply Dr. Jackson is dedicated

to understanding both the Islamic historical, legal and theological tradition

as well as the contemporary reality of Afro-American Muslims. He also works

tirelessly to eradicate the misconceptions and hostilities towards Islam and

Muslims in the US.

Keith Maurice Ellison (b. 1963). A member of the Democratic Party, Keith Ellison

became the first Muslim in US history to be elected to Congress (as the

representative for Minnesota’s 5th Congressional District). He

was sworn in on an English translation of the Qur’an that once belonged to

former US President Thomas Jefferson.

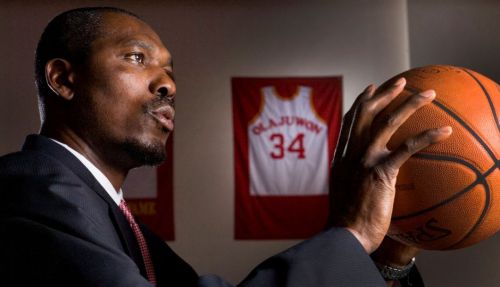

Hakeem Olajuwon (b. 1963). Of Nigerian descent, Hakeem Olajuwon is one of the

most widely recognized and influential Muslim athletes in the United States. He

played as center for the Houston Rockets and Toronto Raptors between 1984 and

2002, and in 2008 he was inducted into the NBA Hall of Fame. He is the only

player in NBA history to be awarded NBA MVP, Defensive Player of the Year, and

Finals NVP in the same season. Olajuwon was (and remains) a deeply committed

Muslim, and would observe the monthly fast of Ramadan during the NBA season

(often playing while fasting).

Share this:

No comments:

Post a Comment